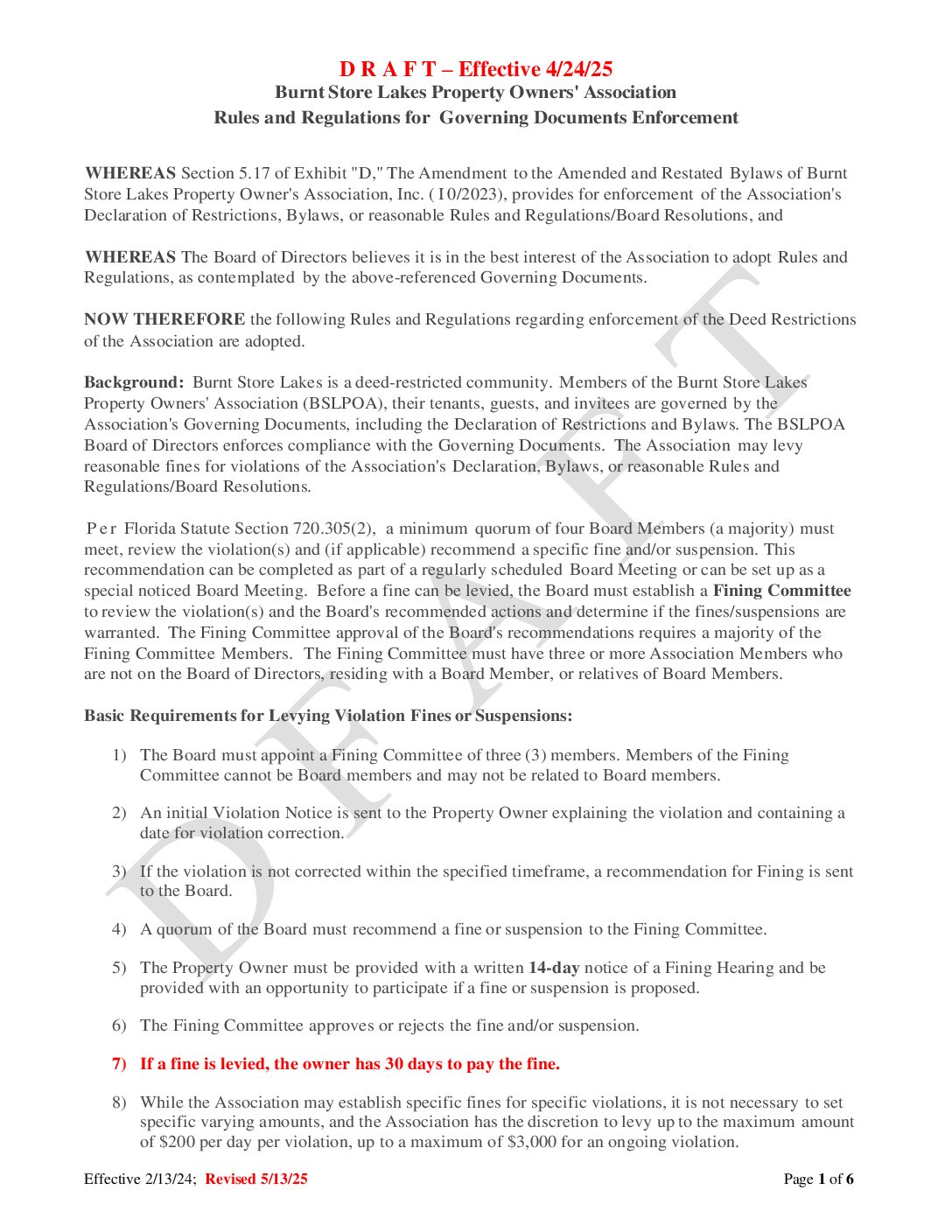

PHOTO TAKEN THE DAY THE SANIBEL LIGHTHOUSE WAS RELIT AFTER SUFFERING DAMAGE FROM HURRICANE IAN.

The stories of Florida’s lighthouses illuminate history and hope.

They are sentinels of safety for ships at sea, but lighthouses provide much more than a safe passage over reefs, rocks, and shoals. They illuminate not only the night sky but the history surrounding the area in which they stand. Communities consider them icons, symbols of where they live, their lights slicing through the night sky and flashing in welcome as you approach the coast.

Lighthouses are a necessity in Florida with its 8,400 miles of coastline, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. With many of those miles having treacherous reefs and other navigational obstacles offshore, ships could not ply these subtropical waters without their help.

There are 30 lighthouses in Florida today, according to the Florida Lighthouse Association, each with its own history and place in the community. The following is the history of the Sanibel Island and the Charlotte Harbor lighthouses.

Sanibel Island Lighthouse

Charles LeBuff has been closer than almost anyone to the life and times of the Sanibel Island Lighthouse – physically and literally. LeBuff lived there with his family, in lighthouse quarters 2, from 1958 to 1979.

The longtime local author, historian, wildlife advocate, and biologist has enough stories to write a book, and in fact, he’s written many, including The Sanibel Island Lighthouse: A Complete History. The facts in this story were drawn from his book and an interview with LeBuff.

Sanibel was often called Sanybel or just Sanib’l in the early years. The lighthouse was first constructed in 1884. It is still used for navigational purposes 141 years later.

But the path to construction wasn’t easy. It took two requests to the government starting in 1856, and several delays until Congress finally established the Sanibel Island Lighthouse Reservation in 1883 and appropriated $50,000 to build a lighthouse station complex on the island.

In the meantime, the parts and pilings for the wrought iron light tower were being shipped to Sanibel from New Jersey, along with a second set of parts for another lighthouse to be built in the Florida Panhandle. But the ship wrecked on a huge shoal about two miles off Sanibel and broke apart, dumping all the components into the sea. A group led by two lighthouse tenders stationed in Key West came to the rescue and recovered nearly all the parts.

The lighthouse was assembled, standing 98 feet above sea level, along with two lighthouse quarters. Later, a third was added. It was lit for the first time using a specially designed kerosene lamp on Aug. 20, 1884, and the light could be seen from 18 miles out at sea.

The first modern, permanent residents of Sanibel Island were the lighthouse keepers and their families. Of course, you could only get to the island by boat. The Sanibel Causeway wasn’t built until 1963. The first keepers and assistant keepers were employees of what was then called the U.S. Lighthouse Service. Later in 1939, the service was merged with the U.S. Coast Guard, and the keepers became Coast Guard employees. In 1949, the Coast Guard decided to automate the lighthouse and left. There was no longer a need for lighthouse keepers.

After the Coast Guard left the station, they negotiated a revocable lease with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, which wanted to use the lighthouse quarters as housing for the employees of the new Sanibel National Wildlife Refuge. The refuge was established in 1945, but the first employees were not hired until years later.

LeBuff became the second person hired at the Sanibel National Wildlife Refuge, after William D. “Tommy” Wood, the first refuge manager. LeBuff remained employed there as a biologist until he retired in 1990.

The employees were required to live in the lighthouse quarters as a condition of employment. The lighthouse grounds were now part of the refuge, but the Coast Guard would still maintain and operate the automated light.

Living at a lighthouse on the beach was wonderful; however, the living conditions were not. For the initial years, the only potable water available was rainwater collected in cisterns. There was no air conditioning and no telephones. Obviously, plumbing, air conditioning, and phone service came later.

But the rent was cheap. LeBuff wound up paying $8 per month for rent.

There were only about 440 year-round residents on Sanibel at the time LeBuff was there. You knew everybody. When a car was passing by, you’d wave. In 1960, LeBuff was the 155th person to register to vote on Sanibel.

The refuge was later renamed the J.N. Ding Darling National Wildlife Refuge in honor of the newspaper cartoonist and environmental advocate that pushed for its creation.

The Coast Guard provided a key to the lighthouse to refuge employees in case someone from the Coast Guard had to come down and service it. The key was kept in LeBuff’s office, and he freely used it. “If I had company coming, I’d take them up in the lighthouse,” he said. He was also able to watch the launch of every Saturn moon rocket from the top of the lighthouse. It was 140 steps to the top. Sometimes the Coast Guard staff would also use the key to take residents up for a look.

One time, the Coast Guard apparently came down to service the lighthouse when LeBuff was away. No one could find the key. So, the Coast Guard cut the lock off, and the lighthouse remained unlocked for years.

The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service decided to vacate refuge headquarters at the lighthouse and move to the new headquarters on Sanibel Captiva Road. Upper management decided that the lighthouse property was no longer compatible with the refuge’s objectives.

In 2010, the U.S. Bureau of Land Management sold the land and structures of the Sanibel Island Light Station to the City of Sanibel for $447.70.

Over the years, the island and its lighthouse were no strangers to the wrath of hurricanes. Sometimes the lighthouse became a shelter of last resort.

This happened in 1944 in the days before hurricanes were named and estimated wind speeds were calculated in advance of a coming storm. But it was clear from atmospheric conditions that a bad storm was going to hit. On October 19, many islanders made their way to the lighthouse quarters to ride out the storm.

By today’s standards, it was a Category 4 storm that dropped to a Category 3 by the time it made landfall. However, the surge was starting to lap on the main support beams underneath the buildings. When the wind lessened as the hurricane eye approached, they crawled across the porches and up the stairways leading to the lighthouse’s stair tube.

Eyewitness accounts say the tower swayed in the wind and the sound was deafening as the wind howled through the lighthouse support structure.

One can only imagine what the wind sounded like 78 years later as Hurricane Ian battered the lighthouse with a 15-foot surge in 2022 and broke off one of its legs. But it still stood. The light was relit Feb. 28, 2023, with a temporary prosthetic wooden leg replacing the broken one until the new leg was fashioned. However, the lighthouse quarters were swept into the sea.

Today the lighthouse is significant as a historical object and is the oldest structure on Sanibel.

Charlotte Harbor Lighthouse

The Charlotte Harbor Lighthouse in Charlotte County could be called the “ghost” lighthouse, since all that remains of it is a navigational structure composed of a single steel piling, with a flashing red light to mark the spot where it once stood.

“The lighthouse’s isolated location in the center of the wide bay and its relatively short lifespan have caused this lighthouse to be one of the least well known in Florida,” according to a 2007 story written for the Lighthouse Digest magazine by Neil E. Hurley, who has served as historian for the Florida Lighthouse Association.

The South Florida railroad selected Punta Gorda as its southern terminus, but the first train didn’t arrive until July 24, 1886, Hurley wrote. Then Congress passed an appropriation in 1888 for $35,000, which allowed for what is now the Port Boca Grande Lighthouse and the Charlotte Harbor Lighthouse to be built. The idea was for a fleet of steamships to connect Florida from Punta Gorda to southern ports in Cuba and the Caribbean.

The Charlotte Harbor Lighthouse, completed in 1890, stood on a cast-iron foundation that provided a landing area just a few feet above sea level, Hurley wrote. On top of the foundation, the wooden lighthouse was a square, one-and-a-half-story structure, with an iron lantern at the top, painted black. The light was a fixed, not flashing red light that was 37 feet above mean sea level. A 16-foot boat was hung on the side of the lighthouse for the use of the keeper.

The lighthouse marked the location of Cape Haze Shoal, which is still a hazard to boaters today, said Frank Desguin, president of the Charlotte County Historical Society. “The shoal extends way out into the harbor off of Cape Haze,” he said. The lighthouse’s light was visible for 11 miles.

The only problem was that the waters of Charlotte Harbor Bay are shallow, ranging from eight to 20 feet deep, Hurley wrote. The lighthouse was in water 10 feet deep. It took dredging to eventually build a channel 200 feet wide and 12 feet deep to the docks at Punta Gorda.

When phosphate deposits were discovered near the Peace River, a new railroad was established to transport it for use as a fertilizer. The Charlotte Harbor and Northern Railroad took the mined material to a deep-water wharf at the southern tip of Gasparilla Island. “The new wharf could handle ships with a draft of 24 feet, doubling the depth of water that was available at Punta Gorda,” Hurley wrote. “The amount of shipping going to Punta Gorda steadily declined.”

The Charlotte Harbor Lighthouse was manned for only 28 years. In 1911, the light was changed over to an acetylene gas light, which was a fixed-flashing white, Hurley wrote. A 206-day supply of the fuel could be stored on the landing platform underneath the dwelling. In the meantime, the usable depth in the channel had been reduced from 12 feet to 10 feet due to shoaling or sediment deposits. Near the Punta Gorda wharves, the water was only 7 to 9 feet deep, Hurley wrote.

Since there were fewer ships and the acetylene gas lamp was reliable, it didn’t make sense to have a manned lighthouse. In 1918, the keepers left, and the light continued to operate automatically.

The unmanned lighthouse continued operating until 1943, Hurley wrote, but years of neglect had left the tower badly deteriorated. It was decided that demolition was cheaper than restoration.

However, Desguin said the keeper’s house itself was spared, barged to shore at Tarpon Inlet and is still used as a residence today.

The cast-iron pilings for the foundation were removed in 1975 and replaced by a single steel piling. The number 6 was added to the piling and the official name became Charlotte Harbor Light 6. It still operates with a flashing red light.