THE SCIENCE, STRATEGY, AND STING BEHIND MOSQUITO CONTROL AND KEEPING RESIDENTS ITCH-FREE

Mosquitoes have one mission: to bug us.

They may be small, but mosquitoes can quickly become a buzzkill to summer plans, from humming in your ear during morning walks to taking a bite out of your backyard barbecues.

Visitors and locals are drawn to our sunshine, surf, splash-worthy lakes, and pools. However, we are not the only ones who enjoy these buzzing hotspots—mosquitoes are frequent flyers there, too. While some folks manage a few heroic swats, others quickly become bug bait from May through October.

“Some people are more prone to mosquito bites than others. While it is not conclusively proven why this happens, things like sweat, body odor, body temperature, and carbon dioxide output are likely contributing factors,” said Dr. Keira Lucas, deputy executive director for Collier Mosquito Control District.

Fortunately, local mosquito experts don’t just bite back—they bring the sting. Equipped with practical methods, they share proven strategies to fend off pesky mosquitoes.

BUG BASICS

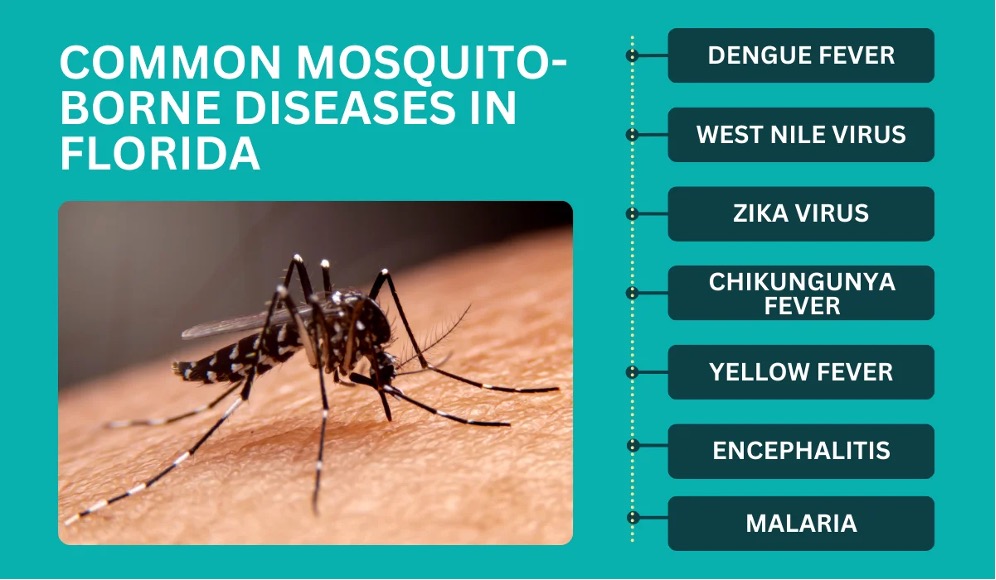

Ryan Sullivan, an environmentalist with Palm Beach County’s Department of Environmental Resource Management and Mosquito Control, said there are about 3,500 mosquito species worldwide, with nearly 90 found in Florida. While some animals might occasionally feed on them, they’re not considered a keystone species and are relatively poor pollinators compared to other insects.

“New species are discovered frequently,” said Sullivan, who has over six years of experience. “We commonly see around 30 different species in our areas, while others appear only sporadically.”

“Each species has unique and different host preferences. Some mosquitoes rarely bite humans because they primarily seek and feed on birds or amphibians, despite being widespread and ubiquitous. Interestingly, under a microscope, some mosquitoes reveal beautifully colored patterns and specifically target creatures like leeches or worms.”

The tiniest of them all is the Uranotaenia lowii, measuring just 2.5 millimeters long. But the real culprits are the state’s top five behind most bites: the yellow fever mosquito (Aedes aegypti), the fierce Asian tiger mosquito (Aedes albopictus), the southern house mosquito (Culex quinquefasciatus), the black salt marsh mosquito (Aedes taeniorhynchus), and the giant gallinipper (Psorophora ciliata).

“Mosquitoes and biting midges (no-see-ums) are two different species of biting insects. The biting midges we have here in Florida are not known to carry disease, and people can use the same EPA-approved repellents to protect themselves from their bites,” explained Lucas, noting that control districts focus solely on mosquito activity.

REPELLENT RESPONSES

Florida’s humid climate and lush environment keep mosquitoes active year-round. As a result, mosquito control districts statewide conduct ongoing surveillance and use a mix of proven and advanced methods to manage populations.

“Mosquito populations are always going to vary year-to-year depending on environmental factors such as coastal tides and the amount of rainfall,” Lucas noted. “We will not treat in inclement weather for the safety of our team and to ensure the treatment is effective. If treatment is delayed due to the weather, we will perform the treatment as soon as possible after the weather passes.”

The Lee County Mosquito Control District, which also covers parts of Charlotte County, began using the sterile insect technique (SIT) in the 1950s to target screwworm flies. In 2016, it expanded SIT to mosquitoes, launching on Captiva Island in 2020.

“This program releases sterilized male Aedes aegypti, with the goal of them mating with wild females. Any resulting eggs will be nonviable,” Lucas explained. “The process is similar to spaying or neutering pets. …”

“SIT involves using an X-ray machine to irradiate male mosquitoes inside laboratory cages,” Sullivan said. “The goal is to suppress the population by reducing the most prevalent species.”

THE BUZZ DISTRICTS

Each mosquito control district manages diverse areas, from neighborhoods to remote wildlife zones. Aerial inspectors use helicopters to survey marshlands, while ground members monitor breeding sites and respond to service calls. During peak season, trap trucks operate frequently to screen mosquito activity and rainfall, targeting affected areas.

“This year, we are seeing an increased number of salt marsh mosquitoes,” Lucas said. “These are common in the spring and early summer when the high spring tides inundate the coastal mangroves and grasslands.” These mosquitoes emerge in large population explosions after dry winters, which is what we experienced in the last four months.

The experts noted that Florida’s west coast tends to have more mosquito breeding grounds due to its swamps, mangrove forests, expansive salt marshes, and heavier rainfall. In contrast, the state’s east coast has seen lower mosquito numbers this year, largely due to a drier summer and more developed residential areas, particularly from Jupiter to Boca Raton.

Wetlands are prolific breeding grounds for mosquitoes and require targeting mosquitoes in their aquatic stages before they develop into biting adults. Officials say adult mosquito activity is monitored from May to October, with control measures implemented when thresholds or disease risks are detected.

Sullivan said trap data helps track mosquito trends using a population index. Residential areas are treated by truck, air, or drone. Ultra-low-volume spraying targets larval and adult mosquitoes with under an ounce per acre, minimizing harm to other species.

“Treatment frequency shifts with mosquito population levels,” Lucas said. “Coastal areas typically see the highest numbers in late spring and early summer when black salt marsh mosquitoes hatch in large broods after high tides trigger dormant eggs in mangrove beds. These mosquitoes can travel 40 to 60 miles with the wind.”

During Florida’s summer months, mosquito complaints typically increase. To monitor activity, teams set up temporary light traps in private yards. If a trap collects 25 or more mosquitoes, it can prompt a nighttime spraying mission in that area.

BLOCK THE BITE

Regional mosquito control agencies use an integrated pest management (IPM) approach to control mosquitoes and protect public health. This system combines monitoring, treatments, biological tools like mosquitofish and SIT, research, and disease testing.

“Residents are an important part of our IPM plan as well,” said Lucas. “That is why we participate in hundreds of hours of public outreach and education every year to help empower residents and visitors to protect themselves and their properties from the threat of mosquitoes.”

Lucas recommends following the “5 Ds of mosquito control”:

• Drain: Drain standing water from containers around your home.

• Dress: Wear long sleeves and long pants when it is reasonable.

• Defend: Use an EPA-approved mosquito repellent with DEET, picaridin, oil of lemon/eucalyptus, or IR3535.

• Dusk and dawn: Avoid being outdoors when mosquitoes are most active.

The county mosquito control districts advise residents to eliminate standing water from everyday household items like buckets, children’s toys, potted plants, and birdbaths.

There are two methods for controlling mosquitoes in plants: thoroughly flushing the plants once a week to wash away any developing larvae or using a granular insecticide labeled for mosquito control.

“Mosquitofish are a great option for small areas of contained water that can’t be dumped, such as swales, rain barrels, abandoned pools, and livestock troughs. They are native to Southwest Florida, and each fish can eat up to 100 mosquito larvae a day,” said Lucas.

The control districts use mosquitofish as a natural alternative to chemicals. Surviving up to three years, the small freshwater fish begin feeding immediately after hatching and tolerate a wide range of temperatures.

The professionals advise anyone who suspects a mosquito-borne illness to seek medical attention immediately. Noting that mosquitoes can also affect pets, with heartworm posing the most significant risk to dogs and cats, while horses are vulnerable to West Nile virus and eastern equine encephalitis (EEE). Preventive steps include administering regular heartworm medication, keeping animals indoors during peak mosquito activity, and ensuring horses are vaccinated.